Tradition, religion and identity: In the Land of the Thunder Dragon

This is part three of a three-part series called In the Land of the Thunder Dragon exploring the culture of archery in Bhutan. Part two is An Olympic flagbearer and part three is Tradition, religion and identity.

The bow and arrow is an essential part of the Bhutanese imagination, in a land where recorded history only started a few hundred years ago.

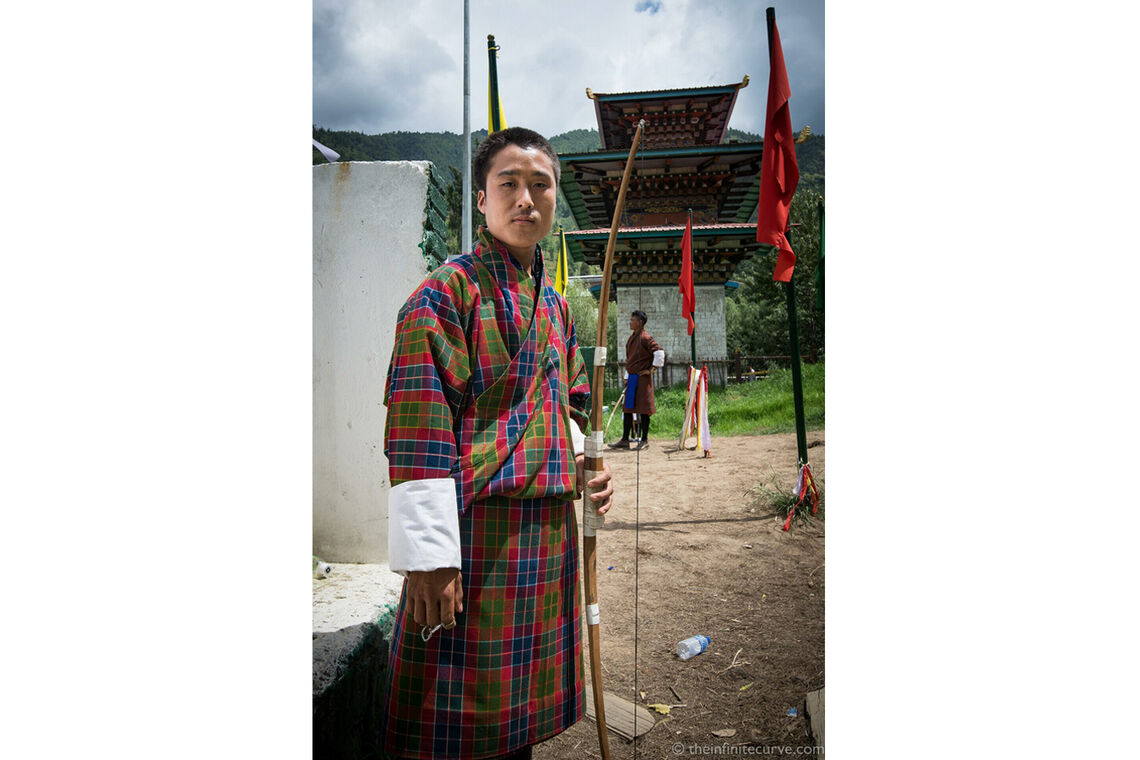

Many countries have archery traditions based on the military or the nobility. In Bhutan, these traditions are tied together with national identity and religion to make a potent symbolic cocktail.

The bow was a hunting weapon for millennia until the arrival of modern Buddhism began making archery a cultural outlier, a martial art among a population that disapproves of killing.

(Many Bhutanese eat meat, but most of the butchery is done by foreign workers).

Arrows are used as offerings and religious relics alike, and ritual arrows, or da, mark significant events such as the birth of children.

As a military weapon, it played a dominant role in the many skirmishes in the region. In feudal times, militias of bowmen were raised from local warlords, all commandeered by a mdaa-dpon, or ‘arrow chief’.

Many times this tiny nation has been attacked by invaders, usually from Tibet, and each time the invaders have been driven back in a hail of arrows – at least according to legend.

The bow is literally the protector of the state. In more recent times, an arrow shot by the father of the first king is said to have killed a British general in 1864, after the British attempted an ill-advised military adventure in Bhutan related to the annexation of India.

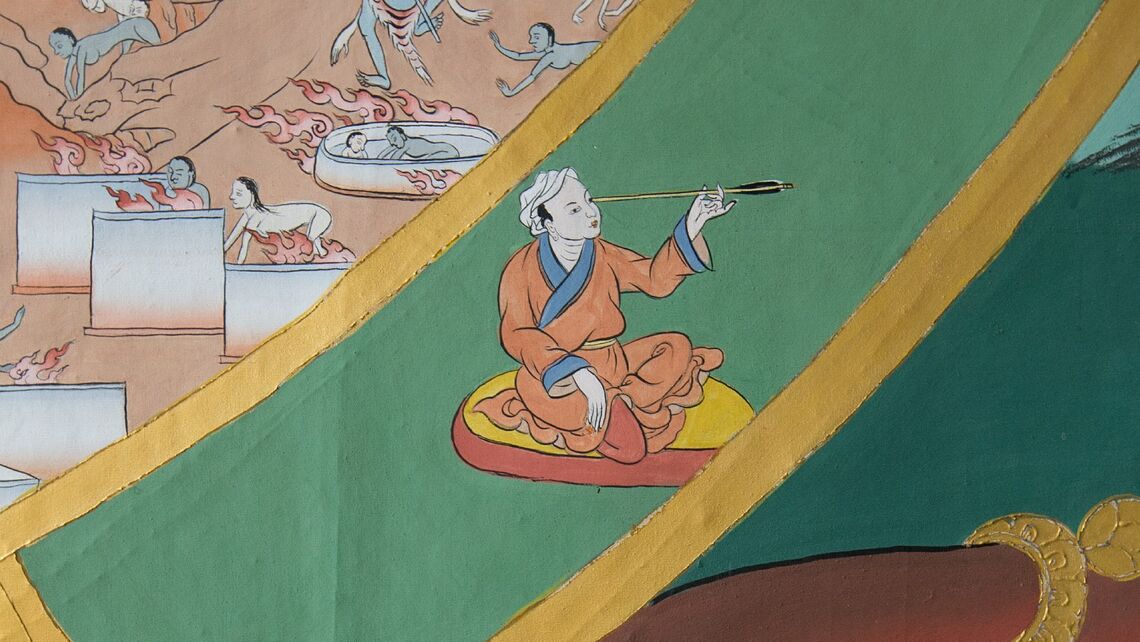

As a Buddhist symbol, the bow and arrow is found throughout the art, mythology and theology of the region; held by gods, part of vivid legends, lauded in sacred texts and painted on the walls of the dzongs, the temple fortresses.

Guru Rinpoche, an eighth century teacher some say was a reincarnation of the Buddha himself, was said to be able to “shoot an arrow through the eye of a needle. He could shoot 13 arrows in a row, one hitting another, and the force of his arrow could penetrate seven doors”.

The Bhutanese are very proud of a 10th century tale about the assassination of the Tibetan Emperor known as Langdarma, who persecuted Buddhists in the region.

A monk called Lhalung Pelgi Dorji travelled to the Emperor’s court, performed a dance to entertain him, then quickly drew a bow from the voluminous sleeves of his costume and shot the persecutor dead.

The story, if true, holds much that the Bhutanese hold dear: the protection of Buddhism above all; a kind of practical cunning; and the bow as protector of the nation.

The ‘Black Hat Dance’, complete with big-sleeved costume and bow, is a key part of the folk culture and is performed at the major festivals (tshechus) throughout the country every year.

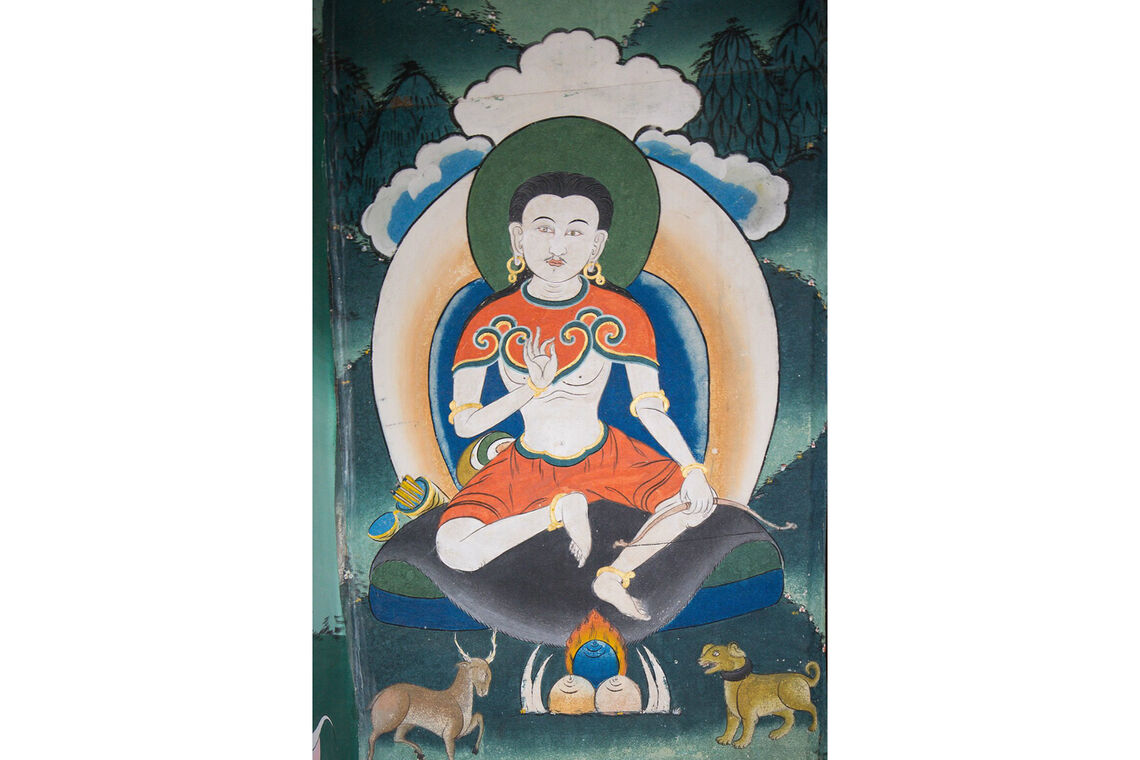

One of the most celebrated historical figures is the ‘Mad Monk’ Drupa Kinley, a 15th century lama known for preaching a raucous, sexually-charged, heretic take on Tibetan Buddhism. Usually depicted with a bow and arrow which he used for divination, he was supposedly a great hunter who never missed.

(Visitors to his temple in Punakha are routinely touched on the forehead with his iron bow and a wooden phallus.)

Drupa Kinley represents the rural, earthy, raw side of the Bhutanese character, reflected in the distinct branch of Buddhism in the country, entwined with an earlier animistic and shamanistic religion called Bon. The raucous, macho, rude nature of traditional archery echoes his character today.

In the 20th century, the sport was further popularised by the various kings of Bhutan, all apparently enthusiastic archers.

The second king, Jigme Wangchuck, crowned in 1926, was said to enjoy shooting continuously for over 20 days. It became a sport for the nobility as well as the people, and spread even further.

Archery is now officially enshrined as a vital cultural tradition, although ‘tradition’ in Bhutan is a fluid, moveable feast among such a practical, self-sufficient people.

----

It’s late afternoon on Sunday. We’re at the main archery field in Paro, Bhutan’s second city and the home of its single international airport.

Fittingly a team from DrukAir, the flag carrier airline, is playing a local team from Shari. The match is well into its second day and looks set to be heading over into Monday. I ask my guide: “don’t people have to work?”

“Yes, bu… well, archery usually takes priority,” he replies, smiling.

There are perhaps 150 spectators here, all locals. You can watch matches for free, and people spend long, lazy afternoons dropping in and out, drinking tea and eating at the small canteen.

Unlike most other Asian nations, no one is smoking – cigarettes are all but banned here, part of a paternalistic series of measures put in by the government.

There’s a lot of chewing; many people chew the vividly coloured betel-nut, which has a stimulant effect, and evident in the red spit around the range. There are at least a dozen or so monks watching in their distinctive orange robes and shaven heads – all wielding smartphones.

The match has a grittier atmosphere than the one in the capital. More at stake. More drama.

Previously, I’d seen the use of gleaming new compound bows in traditional archery as jarring – at least, perhaps, with the Bhutan of my imagination.

I ask Ugyen Rinzin why compound bows are so popular.

“I think it’s partly modernisation,” he says. “The love of the sport has always been there. It’s not like archery is more popular now than before, but the overall income has increased, so people are able to afford more bows, and so there’s more people interested in compound archery.”

The culture is the same, as are the rules of the game. The compound bow is just an improved tool for getting there.

A compound bow shoots faster and more accurately with less training. The goal of archers is to play and win; and the expensive bows are status symbols. It’s a reflection of 21st century Bhutan: a keenness to cherry-pick the best of the outside world and fuse it to the utterly distinctive culture already in place.

There is a deep strand of pragmatism here, and archery in particular has a dominant, showy culture which will not stand still.

Archery has been growing in recent years, but faces challenges ahead.

“Other sports, like football, are in schools now,” says Rinzin. “People are exposed to more things. Children growing up in the city, in Thimphu, don’t grow up with archery like they might have done before.”

I wonder how long this distinct culture can survive the complex array of forces that the opening up of the country has begun; smartphones are now almost as ubiquitous here as anywhere else on the planet.

But right now, archery seems in strong health. The passion for the sport is evident everywhere. It is indeed, in the blood.

----

“The love that is shared by all: royalty, farmers, civil workers, business people and that is manifested in our local lore, in art as symbolic weapons of deities, in our beliefs as something that divine can control and something that we the Bhutanese have been blessed with. The archery is in our blood.” – Yangphel archery website.

----

John Stanley’s three-part In the Land of the Thunder Dragon series explores the culture of archery in Bhutan. Part one is called Archery is in our blood, part two is An Olympic Flagbearer and part three is Tradition, religion and identity.